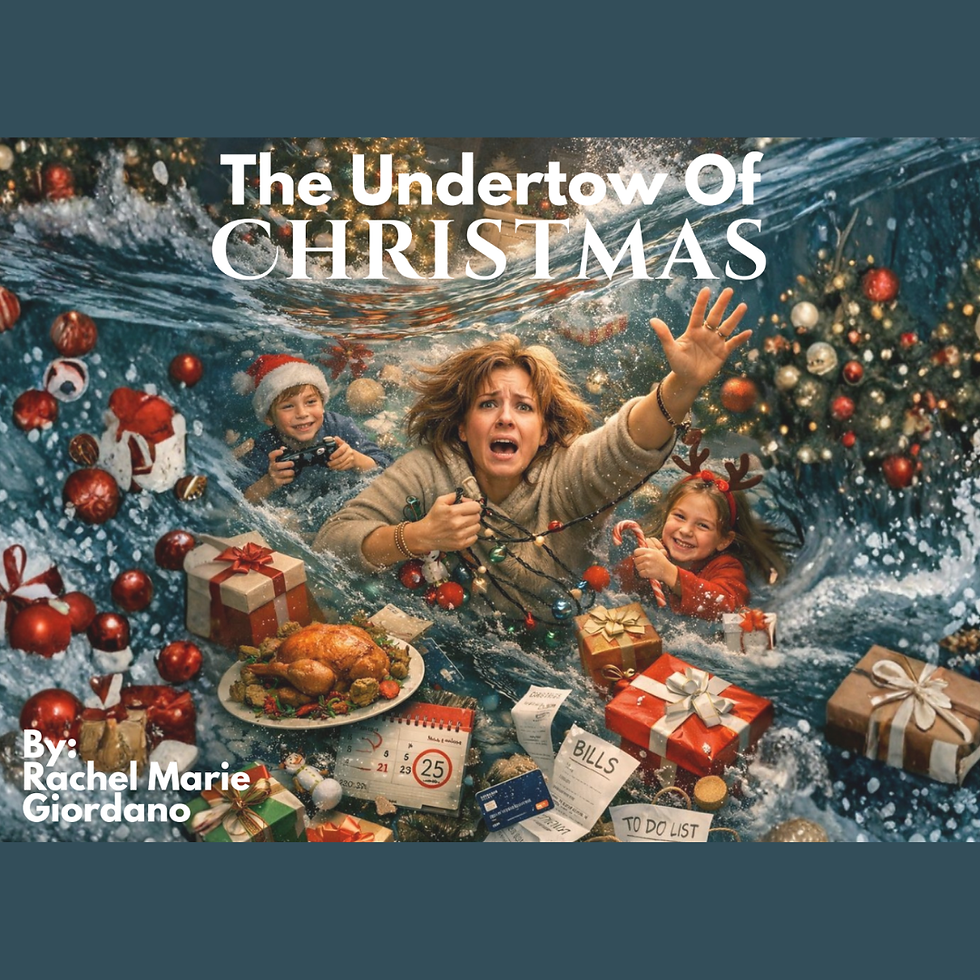

THE UNDERTOW OF CHRISTMAS

- Rachel Giordano

- Dec 23, 2025

- 4 min read

There is a version of Christmas we are shown, and then there is the version many women are living in daily.

The visible Christmas is warm and cinematic. Twinkle lights. Coordinated pajamas. Tables that look effortless but never are. Children glowing with anticipation. Traditions that appear to arrive fully formed, as if by magic.

The invisible Christmas is carried.

It lives in lists that never stop running. In mental tabs left open for weeks. In emotional labor that begins long before December and doesn’t fully resolve until well into January. It lives in women who are the infrastructure of the holiday; the planners, the rememberers, the smoothers, the fixers, often holding everything together by a thread that no one can see.

I want to talk about that undertow.

The part of Christmas that pulls quietly beneath the surface.

As someone married to a man who openly dislikes “Hallmark holidays” which somehow allows him to automatically opt out, I’m aware that I’ve taken on this work largely on my own. He works incredibly hard to provide for our family, and I’m deeply aware of the weight he carries in his own way. And, I suspect, that even if he loved holidays, I would still find myself carrying the responsibility of making everything feel magical.

The Unseen Labor of “Making It Magical”

We often say Christmas is magical, but we rarely interrogate where that magic comes from.

Magic, in practice, is labor that disappears once it’s done well.

It is knowing who likes what and who doesn’t speak to whom and how to seat people so tension doesn’t erupt before dessert. It is remembering the teacher gifts, the wrapping paper, the tape, the batteries, the cookies that must be made because they are always made. It is emotional choreography, anticipating disappointment before it happens and absorbing it when it does, counting gifts to ensure each child has “enough,” even when no one can quite define what that means in a child’s eyes, which are shaped as much by anticipation as by what’s actually under the tree.

This labor is rarely assigned. It is assumed.

Some expectations are placed on women externally, by family, by tradition, by culture. Others are taken on internally, inherited through modeling and memory. We watched our mothers do it. We absorbed the message early: if the holiday falls apart, it’s because you didn’t hold it correctly.

So we hold harder.

Even when we are exhausted.

Even when we are grieving.

Even when we are financially stretched.

Even when we are already at capacity in every other area of life.

The cost of Christmas, for women, is not only time or energy. It is the quiet pressure to perform emotional stability for everyone else.

Holding It Together by a Thread

What often goes unseen is how thin that thread can be.

Women are navigating work deadlines, caregiving, relationship dynamics, health issues, and grief, then layering Christmas on top of it as if it exists in a vacuum. As if December arrives without context.

There is very little space in the cultural narrative for women who love Christmas and find it overwhelming. For those who feel joy and resentment. Gratitude and anxiety. Celebration and a sense of being cornered by expectation.

So many women don’t say they’re struggling. They say they’re “just tired.”

Tired is the socially acceptable word for emotional overload.

But beneath tired is often fear, of disappointing others, of breaking tradition, of being seen as ungrateful or insufficient. And beneath that is the reality that the holiday is frequently propped up by women who are running on reserves.

The Budget No One Talks About

Then there is the financial undertow.

Christmas spending is rarely framed as neutral. It is moralized.

For some people, there is an unspoken equation that ties love to expenditure. Thoughtfulness with price. Sacrifice with worth. Women, especially mothers, often feel this acutely. Not because we are fiscally irresponsible, but because the emotional stakes have been set so high, heightened by our own impulse to present a picture-perfect Christmas morning and visible abundance beneath the tree on social media.

Budgets stretch. Credit cards absorb the overflow. January becomes the reckoning month no one posts about.

What’s striking is how often women are the ones carrying the emotional responsibility for the budget and the emotional fallout of not meeting imagined standards. They are the ones trying to make the numbers work while ensuring no one feels the strain.

Financial stress becomes another invisible task to manage quietly.

Smile through it.

Figure it out.

Don’t let the kids feel it.

Even when the cost lingers long after the decorations come down.

Reclaiming Choice Inside Tradition

This isn’t an argument against Christmas. Or tradition. Or generosity.

It’s an invitation to look more closely at what we’ve normalized.

Who benefits from the current structure of the holiday?

Who is rested at the end of it, and who is depleted?

Which traditions are nourishing, and which are performative?

For many women, reclaiming Christmas doesn’t mean abandoning it. It means choosing consciously instead of inheriting obligation by default.

It means allowing the holiday to be good enough instead of perfect.

It means recognizing that magic doesn’t require martyrdom.

It means letting some things be simpler, even if they look different than before.

And perhaps most importantly, it means telling the truth: that love does not require self-erasure, and tradition should not demand quiet suffering as its entry fee.

Christmas will always have an undertow. That’s the nature of emotionally loaded seasons.

But when we name it, we stop being pulled under by it.

And maybe, just maybe, the magic becomes something women get to experience too, not just create for everyone else.

About The Author:

Rachel Marie Giordano is a media producer, writer, and consultant with nearly three decades of experience in television, radio, and digital storytelling. She creates content about identity, leadership, and the stories women carry, both publicly and privately.

Comments